Manhattan Transfer. Sounds familiar? Boop-bap Boop Bap.

Actually, the successful 70s singing group took their name from a minor classic piece of literature written by John Dos Passos, Manhattan Transfer in 1925. To save you wondering any longer, ‘Manhattan Transfer’ is mentioned once in the narrative, a fleeting reference to a public transport interchange. That’s all!

My impressions of the book take on a necessarily anachronistic colour. I am reading this almost 100 years after it was written. It is the fate of every writer that he gives freely and suffers the ravages of time, time being that thing he cannot anticipate or control. It is only a happy accident that the likes of Kafka and Orwell get now mentioned more than any other person but Hitler. Either they were prophets or they were lucky. But the effect is the same. They could not address the vagaries of the interpretive communities of their day and they certainly could not address those of a century into the future. But being great writers, perhaps they managed to make a good fist of it, by understanding the human condition. The idea of interpretive communities was promulgated by a hero of mine, Stanley Fish. It boils down to the fact that all of us deal in shibboleths; I live in a particular part of Yorkshire where a bap (boop bap boop bap) is called a breadcake. You might call it a bun, a barm or even a roll. People who teach linguistics have to get over the idea that, to us, a mundane item like a table is pretty much a universal thing, but there are places where communities do not have tables - so how would you describe one to a talkative dolphin or a lost Amazon tribe?

So I admit, this is a windy preamble. You and I read a century old novel through the prism of a different kind of brain-training; 50 years or more of television and film - we are hard wired to accept all the messages subliminally and we are trained to deal with television and movies in a way that was not possible before the moving picture came along. Early movie goers ran screaming along the aisles when a short film depicted a train speeding towards the camera. In this respect, the narrative is not as jarring and desultory as its first readers might have found it. Or as shocking.

Dos Passos’ book may have been seen as ground-breaking in 1925, but is it now a mere curiosity? Liberties are taken. Phrases are welded into words. Paragraphs jump-cut like an action movie into other scenes. One critic described it as visual cubism. It’s a carousel of characters wrapped up in a generally bleak montage. Syntax gets artfully mangled. I wondered what people thought of it at the time of publication. Sinclair Lewis declared it to be a ‘modernist masterpiece.’

DP can broadly be linked with Hemingway and Fitzgerald. There are little pulses of the former’s terse, paratactic prose and the latter’s fondness for letting his characters reprise cute aphorisms. There’s a Runyonesque flow of shoity, hotsy totsy, toity toid and toid Bronx dialogue mixed with immigrant patois. It’s buddy, can you spare a dime.

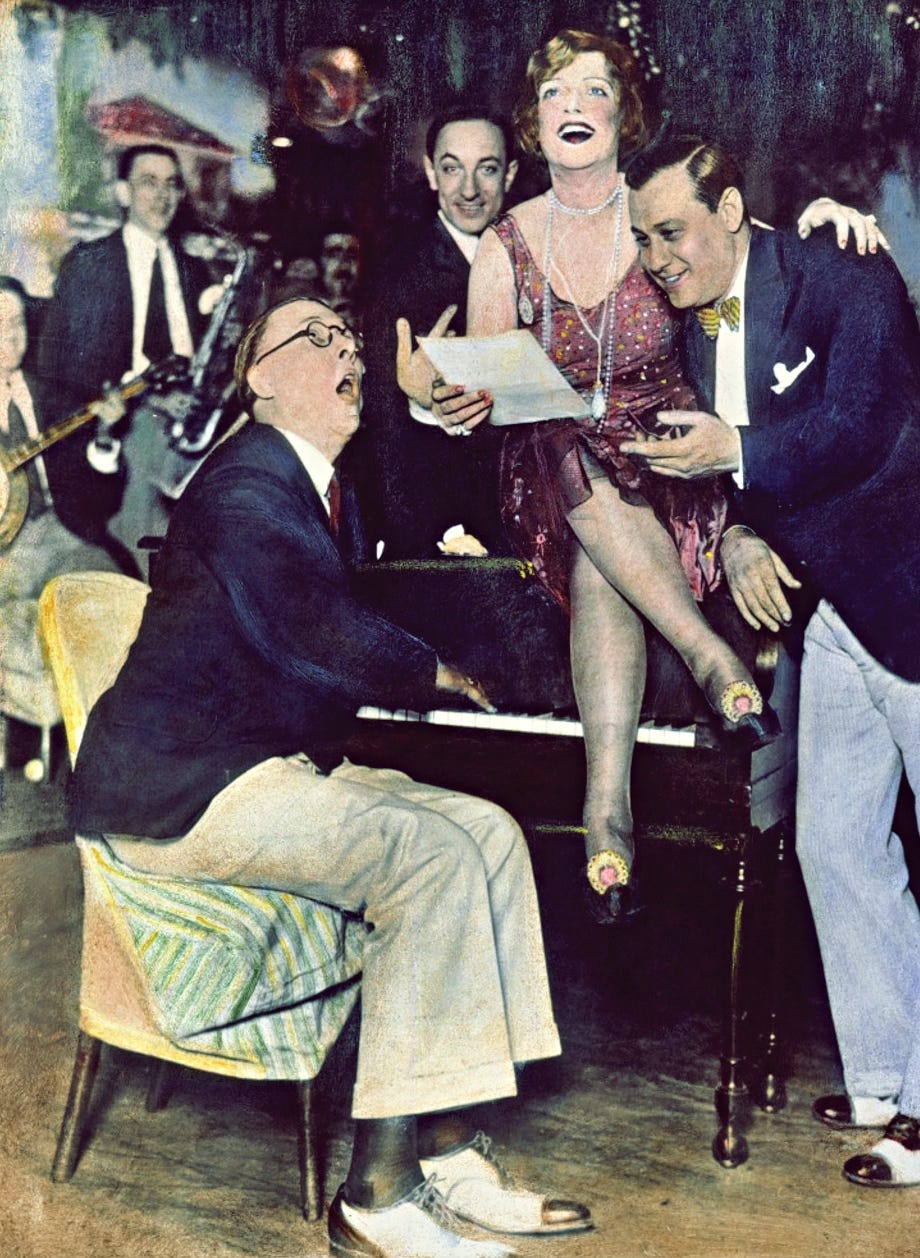

It reads like the visualisation of Edward Burra’s The Band or Hopper’s Nighthawks.

Critically, all of this - the style, the syntax, the frenetic pace, the chiaroscuro works, for the first 100 pages or so, on my re-reading after a gap of 25 years. I skimmed the rest. Sorry, but I have a life. It travels on until the arbitrary end. The constant jumping about from one scenario to another, often without a full stop or a comma, gave me the vapours. Some of the characters have lives you can relate to. Bud Korpenning is one; someone with a back story that is revealed later. Someone born to fail. Someone whose fate turns on a buried phrase in the general collage - blink and you will miss it. (Oddly enough, I caught it, which is probably a testament to Dos Passos’ skill.) Nevada Jones is a sassy actress on the make and a heartbreaker. I quite got to like her, even though she is a piece of work. Hunger and poverty gnaws at the characters. It’s a depiction of people living on peanuts and two-bit breakfasts and cold stew and stale milk. People wanting to step out of a cab in order to impress, but nervously watching the meter at the same time. The sheer misery of being hungry. The irony of being once at the top, like Joe Harland, but being reduced to the status of a bum. All life is in Manhattan Transfer. Read it if you must, or just get a ticket on a roller coaster and drop some acid.